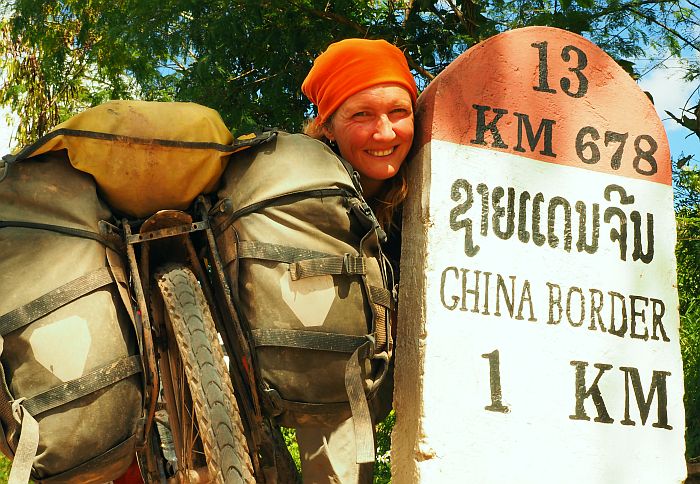

At the border, the customs officials were doing lunch, so I had to wait a while before

I could enter. I got the visa right at the customs counter – valid for 30 days.

One more barrier and I entered the 24th country on my trip in the direction of Australia.

I really didn’t know what to expect; I don’t mean the country, but the feeling I would have inside.

I had been traveling in China for 4 months, and as a goal, I was heading toward the border

crossing to Laos. It wasn’t because I wanted to get out of China quickly, but rather because I

had no choice but to leave the country.

It’s important to have intermediate goals. It’s motivating, they are more tangible and, above all,

milestones are a human attribute. But I had reached my threshold and, therefore, the question

arose: “What’s next?”

Ruediger, a German cyclist, waited just across the border for me. He had discovered me

in my blog and wanted to meet me. Super, some company can always be exciting and so

we cycled together to Luang Namtha. Because of that, I was able to have a lengthy

conversation in German and I was glad for the exchange.

Normally, the first impressions of a new country are particularly interesting, but for me,

the discussion was far more important and, therefore, I took very little notice of my

surroundings other than the many children, who were suddenly everywhere and so

lovingly greeted us with “Sabaideeeee”. They were warm, cheerful sprightly children,

quite unlike those in China.

In Luang Namtha, the Brazilian, Felipe, waited for me, a bloke I had already cycled a week

together with in China, and Julien, a cyclist who I knew from Bishkek and also several other,

really very nice travelers.

I was again among peers, surrounded by people from my own culture. Another world which

has been called the “Banana Pancake Trail” for years. The name stands for the backpacker

scene in South and Southeast Asia.

From then on, I was to meet more tourists than I would prefer.

For the first few days I just took a break. I really didn’t do anything but talking with other travelers.

Laos was to be the country where I could relax for a long break and that’s how it was. Above all,

I wanted to continue to allow my foot enough time to rest, because it just would not heal.

I also asked myself how my trip was going to continue. Australia wasn’t far anymore.

I could easily be in Indonesia for another 2 months and the next country would already

be Australia. No, ending the trip now would be impossible in my mind.

So what should I do?

In Muang Sing, not far from Luang Namtha, the “Festival of Lights” was being celebrated

and absolutely everyone who could possibly make it went there. Felipe and I headed in

that direction again together.

Leaving Luang Namtha, we were caught in heavy monsoon rains. It rained so ultra-hard

for at least 1 ½ hours that it seemed like it had been conjured up by the gods with magic.

It was absolutely amazing to see the water masses thundering down from the sky.

Luckily, we found a large roof where we could stay dry while observing the spectacular

nature show.

The route wound beautifully through dense jungle, past small villages and laughing kids.

The festival itself was unremarkable, because it consisted only of food stalls and a totally

muddy fairground.

I had visited Muang Sing once in 1997. Back then, it was the last backwoods village just before

reaching the end of the world. Today, the Chinese have moved in and bought all the land

surrounding the village and transformed the enchanting jungle into ugly plantations.

The driving style of the Lao people could easily be described as considerate cooperation.

However, as soon as a big car that drove like an executioner appeared, one could always

assume that a Chinese driver was at the wheel.

There are also unpleasant companions here, and although I really love Chinese food,

and it is much tastier than the Lao cuisine, I avoided the Chinese. I didn’t stay overnight

with them, nor did I eat in their restaurants and I also didn’t purchase anything in their shops,

because their standard of living is many times higher than that of the Lao people.

I also had the impression that they are anything but welcome in the country. Because of that,

I preferred to support the local people.

In Luang Namtha they were looking for volunteers to teach English in a tiny school. I imagined

that might be interesting, so I accepted the task gladly. At the same time, a shared garden with

a community house was being built in the village. Everything was being done by Westerners.

I viewed the action with a critical eye, because the guys from Canada, France and England really

went right to it while the local men just watched everything calmly from a safe distance.

For years, these voluntary assignments in the 3rd world countries have been discussed and this

assistance is not always considered to be positive.

When I see the big 4×4 jeeps belonging to the relief agencies around the country, I have my doubts

that the donations were really invested properly.

Around lunchtime, young backpackers would stop now and then with their borrowed canoes

on the village beach. Wearing only bikinis, they would walk around to inspect the village.

Sometimes, I really wonder how people prepare to visit a foreign country and its culture.

We all make mistakes, but I would reasonably assume that a half-educated person would

know that something like that is way off the mark.

We stayed in the small settlement and were treated with food three times a day by the villagers.

Every day, we were guests in another home. Before entering the house, which was often

very tiny, we always removed our shoes, even when the floor was only made of clay.

Sometimes, our food was beautifully served on banana leaves.

The meals always consisted of sticky rice, which I find really very tasty and something you

can also eat cold, because most often, the food arrived cold rather than warm. In addition there

were fried water plants, unfortunately, usually overly salty. If we were lucky, they would also

serve us a delicious, cooked pumpkin.

The village had no shop, no TV, but it had power. A fountain, built by development assistance,

stood in the center of the village. There was no water available elsewhere. The people washed

themselves in the river. To flush the toilet, we used river water – a bucket with a scooping

ladle stood right next to the outhouse. Regardless, the sanitary conditions there were far better

than in China, because the toilets in Laos are clean everywhere.

I camped next to the fish pond in a small bamboo hut and was chirped to sleep by the crickets

at night and, sometimes, I was entertained by the water buffalo grazing on the lawn,

huffing and puffing until late into the night.

The first roosters began crowing as early as 3 o’clock in the morning and the dogs

barked half the night. Regardless of everything, it was wonderfully quiet and relaxing.

There were no engine noises, no shrill TV and no shouting Chinese.

The temperature at night was very pleasant and in the morning, I had to snuggle into

my sleeping bag because, without it, it would have gotten too cold.

The school consisted of three small classrooms, each equipped with a blackboard.

There was nothing but chalk in the school – no paper, no pencils, not even chairs. The only

thing some of the kids had was a small notepad. Together with a Canadian, we tried to teach

the first English words to them. It wasn’t easy.

At the end of the week, they already knew the first letters of the alphabet, the numbers from

1 to 20 and some of the colors. I was excited about every success that we achieved.

I finally had to continue on, because my visa was about to expire again and it was still

a long way to Vientiane. Since my passport was filled with stamps and visas,

the German Embassy was my next destination. I could have left Laos, but I wouldn’t be able

to enter again because the visa for Laos required an entire page.

I chose the gravel road heading directly south, which wasn’t even marked on the map as a trail,

but a few expats confirmed that the road would be passable.

Luckily, my foot was OK again, so I prepared myself and headed into the next adventure.

Once again, it was one of those days where I carried on a conversation with myself. It was a really

bad trail, and I began to fuss. “Why did you do that again? You could easily have taken the

tarmac road, but no, that wouldn’t have been adventures enough. So now you’re in a fine mess

and you can only blame yourself!”

The perspiration was running down my forehead. Puddles, mud and a lot of large stones

adorned the trail, which was spiced up with really steep climbs. It was a mountain bike trail,

but unfortunately, my bike weighs a bit more than a normal MTB. Even the passengers on

some of the mopeds had to get off in some places, because the road was so bad and so steep

that the machines couldn’t make it.

I met only one single pick-up truck; other than that, there was no traffic at all.

My water reserves were exhausted and there was no water anywhere. Finally, I came to a village

and was able to fill up my bottles at the fountain. For safety’s sake, I treated the water with water

purifier tables which I always carry with me as a precaution.

Unfortunately there were no shops in the village, but as always, I had an emergency stockpile

of noodles with me.

It was already late and I asked if I could pitch my tent in the school, which posed no problem

at all. On the contrary, I was warmly welcomed. About 40 kids and a few adults were watching

me as I set up my tent, my cooker and how I sorted my stuff. It was cute how the kids were

amazed at what the falang (foreigner) all dug out of their bags. The cooker, especially, was the

sensation of the evening.

Kindly, they jury-rigged a car battery and a lightbulb for me so I could have some light.

By then at the latest, I knew that I had truly arrived in the 3rd world. Laos is a desperately poor

country, and in the villages, the people really have nothing at all. The children run around with

totally tattered clothing, food is boringly one-sided, the education is surely not very good and

the houses are very small and primitive.

But these people make an extremely satisfied impression. It’s a lot of fun to observe the many

children who bounce around everywhere in all the villages. They run barefoot over hill and dale,

two-year-olds climb around in the trees alone, and they also ride in threes on the village streets

on bicycles that are much too large.

The kids go fishing with small harpoons, they have slingshots around their necks, and even the

very young boys already have large knives with which they cut up everything they can find in nature.

I watched 10-year-olds doing 7 pull-ups on a branch with ease; it was amazing to see

what kind of sophisticated motor skills they have.

Here, children can still be children and the environment is a big adventure land.

The whole village washed themselves in the morning and evening at the village well.

To my surprise, some of the people stood naked under the flowing water.

In the mountainous regions, Buddhism is relatively unknown. Here they believe in spirits

of nature, so for several days, I saw no temples or monks clad in bright orange clothing.

As always, I was rewarded in the end with the choice of which trail to take, because I was in

such remote villages that the children no longer called “Saibadeee”, but rather “falang, falang”

and then ran away from me in fear.

However, I was also often surrounded by a huge crowd of children and was admired to the last

sprocket on my bike. It is incredible how many kids live in such tiny villages.

One night I slept at the police barracks at the end of a small village. The area was so overgrown

that it was really difficult to find a campsite, so the invitation was very welcome. The man spoke

three words of English, and with that, I learned that the last cyclist came through here in February

of this year – about 10 months ago .

The men grilled birds for dinner. Curious, I asked how they caught them. He showed me a box

with the inscription: rat poison. Oh great, enjoy your meal! I declined the invitation with thanks.

That night I put up my tent in the small police station. As always, I left the window wide open

because I at least wanted to have some cool air to escape the heat at night. Children were curious

to see me, but the police officers drove them away.

In the middle of the night, I woke up to a strange noise. From a bag that was not more than a

meter away from the tent, I heard a loud crash. “What’s this? Rats?” I tried to shine my light

into every corner, but I saw nothing. Strangely, I also thought why the rat only began to make

noises at 4 o’clock in the morning. They must have only then come into the house. But how?

I knocked on the floor and made quite a bit of noise, but the creature didn’t stop. A rat would

normally have run away by now. But the beast was so loud, I figured it must be a really large

monster, but nothing moved.

After I didn’t know what to do anymore, I went back to sleep because I didn’t want to fight

with a rat, so I tried to ignore the noise. But soon, the “something” came closer and, eventually,

it was right under my mat. I heard a loud “crack” noise as if someone were chewing on

something hard. “Is this beast now gnawing on my tent?” I lifted the mat high, whacked against

the tent floor and was glad that there was something between me and the monster.

Nothing moved and I saw no bump under me. What’s this? I shined my light once again

to the outside through my little tent window and, suddenly, I saw a large, black beetle

crawling out from under my tent.

“Madness! Is it possible for such a small insect to make such a noise?” Relieved,

I immediately began to laugh and thought, “Yes, you big city Indian. A small beetle was

able to terrorize you and fill you with fear.”

How the trip continued in Laos? I’ll say more about that the next time.

0 Comments