“Are you married?” was the first question I was asked in the country. “No”, I answered briefly. “But you are getting old. You must finally marry now, otherwise it is too late”.

The young man then turned to his buddy and said something in Wolof after which I was told: “Come to my place!”

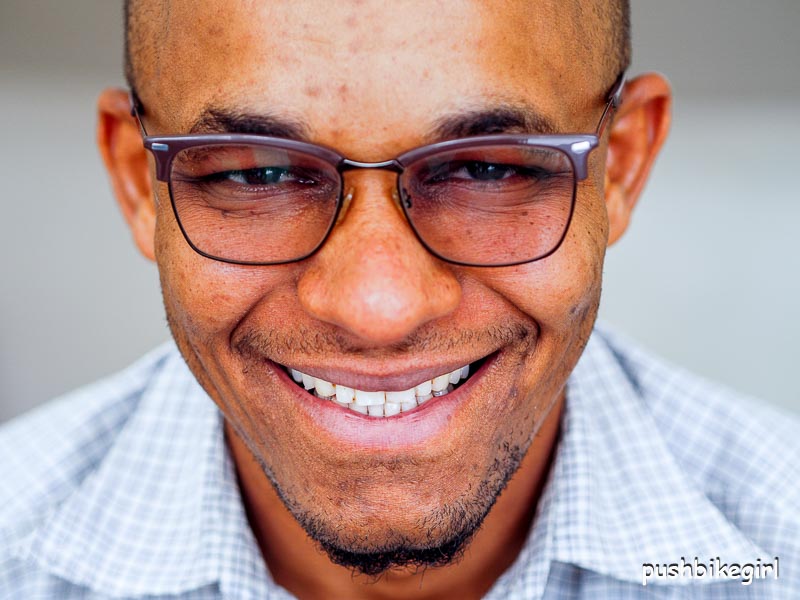

Shortly after this, I met a tall Senegalese man from Dakar. He was visiting the radio station where I was allowed to camp for some time.

“Are you married? Do you have children?” were as always the first questions. My honest answer was then followed by a proper moral sermon, annoying to say the least and as boring as porridge, I said “I’m too old to have children.”

“Too old? How old are you?” was his incredulous retort. “I am 47” I answered honestly.

“Oh, that’s not too old yet! You know what? I’ll help you with that. We can try it and then we see if it works or not” and he smiled into my eyes.

I liked Podor. A small, sleepy town situated directly on the Senegal River. It had a little bit of the old French Colonial flair, exuding a pleasant atmosphere, and so very clean compared to the places I had been in Mauritania.

Of course, there were baguettes everywhere, along with colorfully painted houses and a lot of hustle and bustle.

Every day I was allowed to eat with the two men in the radio station who let me stay there for free from the fourth night on. And so, we sat comfortably together on the floor, spooned out of a common bowl and ate lunch at 2.30 pm and dinner at 9.30 pm.

The food was delicious, but after a short time grew a bit repetitive. Almost always the same dish called Thieboudienne – rice and fish, with different vegetables, with little variation. The fish was often filled with spices and grilled – a small fish for everyone.

Eggplant, a little white cabbage, carrot, potatoes, a little pumpkin, a very bitter – similar to a zucchini but knobby grown vegetable, called bitter tomato and in addition a delicious green paste, also hot chilies.

One evening there was peanut sauce with fish, turned through the mincer served, with couscous. The dish was simply sensational.

I stayed two weeks. Worked on my website, which once again didn’t work as it should but in general, I enjoyed staying somewhere longer and experiencing the African life.

But when the night was turned into day and people drummed all night or a truck driver loaded his truck at 4 o’clock in the morning directly below my window making a huge racket, I actually didn’t get much sleep.

Children visited me almost every evening and checked out what the Toubab was doing. On occasion, goats got lost and somehow found their way into my room on the second floor.

Irritating for sure, when kids threw stones at me and disturbing when I saw women fighting among each other and throwing whole bricks around. But this happened only once.

People here were sometimes aggressive and also very loud when they talk to each other.

The market was colorful, but people were shy when it came to photography and, so I held back.

The heat became more and more a problem and after 10.30 a.m. it was almost unbearable.

I continued along the Senegal River in the direction of Mali. (you can find the MAP here)

“Toubab, Toubab” “Cadeau, Cadeau” was what I heard all day long. So white man white man, gift, gift.

And not only from children.

The first evening I stayed with a family, sleeping on their roof, the coolest place in the night. With a view to the stars and from time to time a breeze it was easy to endure.

The next morning, I had ridden barely 5 kilometers before I was invited again.

I was shown the whole village, shaking nearly everyone’s hand. They all wanted to be photographed and everyone wanted to give me tea and food.

At the end I ate with a woman from Gambia who spoke English and was mothered by her although she was surely 20 years younger than me.

Housework, children, getting water and cooking are her daily tasks. She cooks for three unmarried men from the neighborhood, who contribute to the expenses, but she doesn’t get money for it. Her husband works in Dakar and is therefore almost never at home.

One man asked me if I wanted to marry him. This time I simply turned it around and said to him:

“At your age you are not married yet? Something seems to be wrong with you! Why should I marry you if no other woman wanted to do it before?

The whole village roared with laughter.

Senegalese have a very direct nature and so I was given a bowl of soap and water to clean my pants without being asked.

They also often seemed to have felt the need to discipline me.

In the evening there was open-air cinema for everyone.

Fula’s can be recognized by the two notches next to the eyes – decorative scares. The women are also all strikingly pretty and often wearing lots of jewelry.

Some of them have additionally dyed their mouth parts blue. Really very exciting to look at.

In the small town of Ndioum I bought myself a watermelon, sat down on the side of the road and started spooning out the first half of it when a man came along, sat down, took out his own spoon and helped himself, uninvited.

I continued my journey on some dusty trails through the dry countryside riding past many villages.

The children shouted “Toubab Toubab – cadeau cadeau” after me all day long.

I never got far, because the heat was unbearable. But as always, I didn’t care about the daily distances and Senegal allowed me to stay three months. Enough time to linger.

Every village has a village chief who works for the well-being of the town. Often an old man who deals with possible problems and also receives and accommodates guests like me.

So as soon as the sun went down my contact point in any village was the chief. He greeted me always in a very friendly and respectful manner and assigned me a place where I was allowed to camp.

Luckily, they accepted some of my suggestions and thus I always found a roof to sleep on. First of all, to not sleep directly with the people and secondly it was simply cooler there.

Unfortunately, there were communication problems and therefore in-depth conversation was not possible. But what I have often noticed is that through observation I perceive completely different ideas than when I can really talk.

Often, I see and experience much more because I pay more attention to the subtleties. How do people treat each other, what is the tone of their voices? Observing gestures, who treats whom in what way? Who behaves submissively, who is dominant?

Many travelers also say again and again that it is very important to be able to speak the local language. Of course, this helps immensely and opens more doors, but I recognize the true character and sensitivity of a person better when I see how they treat me when I don’t speak their language. And who speaks Pular or Wolof?

It also shows interest and intelligence when someone deals with me even though they don’t understand me. If you want you can communicate without saying a word – on a completely different level – but this requires patience and imagination and then such encounters are often much more intense and cordial.

For me, countries in which I don’t speak the language are therefore always a strenuous but also an intensive experience, because I am challenged much more. All the more I enjoy it when I can talk again – people just prefer to go the easier way and I am no exception. ?

Until today I still like to remember a Tibetan woman in China who didn’t even try to talk to me verbally. We didn’t speak a word with each other and still we could communicate wonderfully.

Moments that I will never forget and a woman that I have taken to my heart even though I didn’t even hear her voice. Her calm empathetic nature impressed me very much at that time.

So, finding accommodation in Senegal was no problem at all. You really can’t find a place to sleep easier anywhere else. It had been almost too easy.

Further on the way toward Mali, it became clear to me that it might not be the safest place to travel at the moment with its political upheaval and outbreaks of violence. On top of that, Mali was going to be even hotter than Senegal. Since it was already over 40 C hot here every day, I didn’t want to imagine what a few more degrees would feel like.

And so, I crossed Mali off my list for now and soon turned south, because I found the route along the Senegal River okay, but scenically not very impressive. In actuality everything looked the same.

Still on the main road I met an English teacher. He complained that there was not enough traffic on the road. Whereupon I said, “be glad, there is nothing worse than traffic”.

“No, I have to go to school every day and don’t have a car, so I always have to wait for someone to offer a lift. The more cars there are on the road, the more chances I have to be taken along. Sometimes I wait 3 hours” he explained to me.

“How far is home?” I asked.

“Four kilometers”, he said. “Four kilometers? And why don’t you walk or ride your bike, it is much faster. Four kilometers are not far at all” I replied.

“Walking, no, that’s way too far. And with the bike? I don’t have a bicycle and if I did, I would have to buy a very good bike, because otherwise it would be too exhausting and I don’t have that much money,” he explained.

“On foot you would need about 45 minutes, if you would use an old bike you would still be at home in 20 minutes” I added.

“No, I can’t, I’m not as strong as you,” he told me. He himself was a tall, muscular young man.

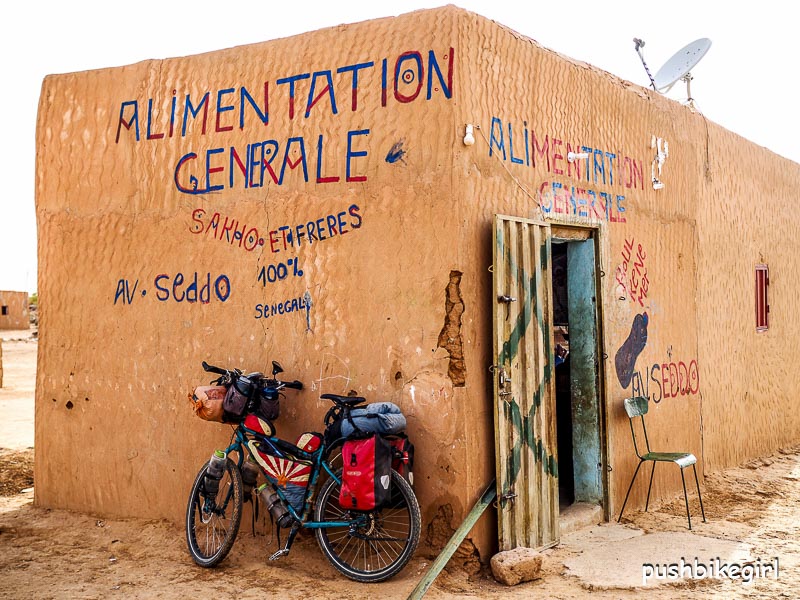

In a shop full of chaos, dirt and dust I wanted to buy something to eat. Four young men sat there on rice bags and buckets and drank tea and one of them greeted me in English:

“Take me to Europe and give me a job” before he even said hello.

Since he was about the 25th guy that day who either asked me if I wanted to take him to Europe or marry him, I was actually already extremely annoyed, I answered him:

“Even if I had a company and could give you a job, I wouldn’t do that because look around here. Your shop is a garbage dump. Instead of sitting here pointlessly, it would be wiser if you would move your ass and do something.” I nearly blew my top that day, because I couldn’t stand hearing the same questions anymore.

In contrast was the widespread practice of sharing. Every day I was asked to eat with them. It was nearly impossible to cycle through any village around 2:30pm without someone calling out to me to come join them around the common bowl.

At first it was hard for me to accept, but at some point, I understood that for everyone here it was perfectly normal behavior. It’s part of the culture.

The culture is therefore not only – ask as often as you can, maybe you will get something – but also that Muslims share and are hospitable. So, nobody goes away empty-handed.

On the one hand this is a very positive thought and honorable, but perhaps it also leads to people feeling wonderfully caught up in it and perhaps not necessarily doing more than they really have to, because in the end they don’t have to go hungry, somebody is taking care of them.

Of course, as a traveler I always have to be careful, because I don’t really know and don’t understand the circumstances and therefore, I can’t judge prematurely.

But it’s often the case that one sees and perceives other things from the outside as a neutral, unbiased observer, rather than as one who has grown up in this part of the world and is trapped in its structures totally unaware how they get stuck in ways that hold them back from a better life.

I saw many sad faces. Not as depressing as in Mauritania, but it can’t be denied that people are having a hard time here.

The road to Tambacounda was marked as a main road and I didn’t really know how remote the area might be. So far there had always been villages and so I assumed it would stay that way.

Where there are villages there are also people and there is something to buy. So, I had very little food with me.

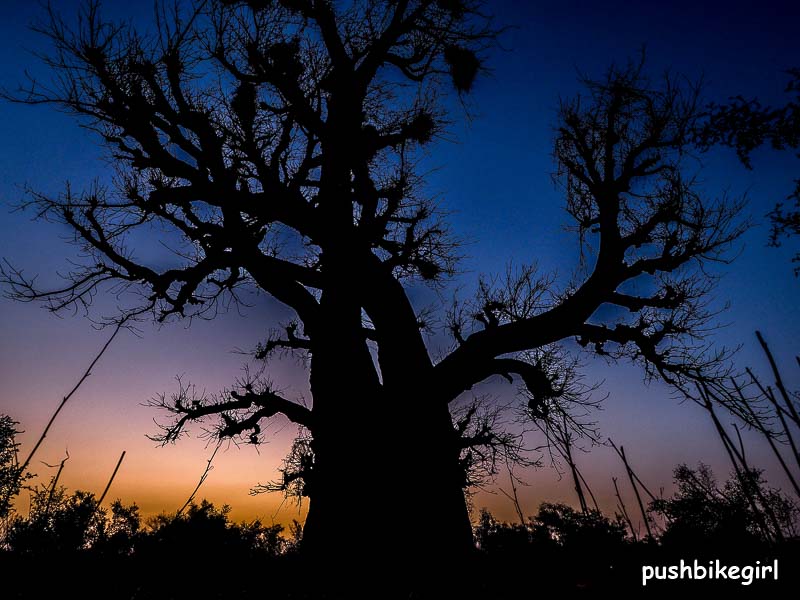

After about 20 kilometers the road surprisingly changed into a path and so it should stay. I was in the bush – finally.

I could camp alone again, cook myself and sleep far better at night. This eternal noise at night is simply not my thing. Whether chickens or screaming children, donkeys or goats someone is always on their feet making noise at night.

The Southern Cross accompanied me now every night and not only that. Shooting stars as well. What was even more incredible was that the first Baobabs appeared. Beautiful trees. Works of art of nature. Gigantic.

Along with the trees came, colorful birds in all variations. The area had something of Australia in it. Red earth and a lot of bush.

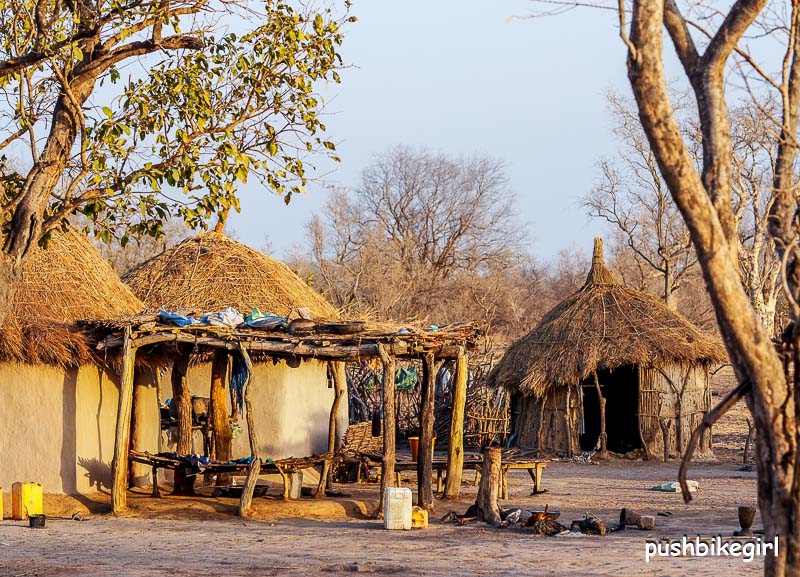

Fula’s also inhabit this part of Senegal. They have vast herds of cattle. They are also extremely elegantly dressed. The villages are tiny, about every 5 – 10 kilometers a few huts appeared. Some are brand new; others are old and starting to decay.

As everywhere in Senegal there are wells. Built by Westerners, providing clean drinking water, which they use for their livestock as well as for themselves. So, I could fill up my water bottles again and again, because I drank up to 10 liters a day at over 40 degrees heat.

Fact was they had a lot of cattle, jewelry and very clean and elegant clothes, but they only had rice to eat. Not even sauce was available. Coffee for breakfast. There was no milk, no meat and not much else. Normally I would say, with the high number of cattle, people must be doing well financially?

I did not find an answer to that.

There was nothing to buy. Nothing at all. There was not a single shop.

I spent one night with a family. I had unpacked my own food as a precaution to show them that they didn’t have to give me anything and I think my train of thought had been right that evening, they didn’t have much.

I was allowed to wash and got a bucket of water pressed into my hand and was sent to the bush. They always pointed to a special place and when I stood near a hole, I wasn’t sure if it was the toilet or the bathroom.

I felt a little stupid. Like such a city dweller that is too senseless to wash in the bush. But the main problem was I did not want to make any mistake. In the end I simply found a spot behind a tree and was glad for the bucket shower.

I didn’t see any toilets anywhere – I assume each one runs to a different tree.

Something else nice here was they all wanted to be photographed. Nevertheless, again I experienced a certain sadness among the people. They weren’t really happy. Something was in the air that I could not interpret.

There were definitely no schools out here. No hospital or something similar. There was nothing here – absolutely nothing.

After about 150 kilometers through the bush I came to a settlement. It was clear from far away that there had to be a shop, because the area was totally littered.

I entered one of the two messy shops and with me half the village. When it’s that hot outside and you’re standing in a tiny shed with 10 other people crushed in, you can really get claustrophobic.

“Toubab Toubab” – the sensation of the month. The whole village was on its feet and everyone wanted to be there.

There wasn’t much available, but there was rice, onions, milk powder and peanuts. And there was a problem, because how do you add these four sums of the individual articles?

I was told “2500 CFA”. Strangely enough, the French numbers were always pronounced differently, I often did not know which number they really meant.

2500 seemed too much to me and so I asked for the individual prices which in the sum only resulted in 1900. Outside the store I wrote the individual prices in the sand, added them and the sum was 1900. But he said again: “No, it is 2500”.

I took the rice, gave him 1000 for it and asked him if that was right? I did that with each item and every time he confirmed it was the right price. In the end he had 1900 in his hand and he said: “No, it costs 2500.

The whole village was there and everyone had something clever to contribute.

At least 50 screaming children ran after me up to the edge of the village and called Toubab Toubab – Cadeau Cadeau and when I arrived at the exit of the village, I saw the sign of an aid organization and now I knew why they begged here again, because in the other villages along the way I didn’t hear that.

Milk powder was really the best solution to hunger in the heat. It really satiates well and is not heavy in the stomach. Perfect.

In the second shop I had bought myself a chocolate bar, which I ate in my tent that evening, tucking the wrapper into my shoes just outside the tent, so that the wind could not carry it away.

Suddenly I heard it rustling and before I understood what had happened, I saw the paper disappear into a hole. Unfortunately, the hole didn’t seem to be big enough, so the rodent hadn’t managed to pull it completely into its den.

So, back in nature, far away from the people and I had to listen to the rustling of the paper for half the night, because the den was only about one meter away from my head.

After 250 great, eventful kilometers and some hot days on this so-called main road through the bush I arrived in Tambacounda and stayed at a missionary station.

The change from bush to city could hardly have been more blatant. The dirt and the diesel exhaust were really no fun, especially not in this heat.

Tambacounda was only barrable for one night and so I left the following morning. But I bought some food beforehand, because who knows when there will be something available again, right?

In the evening I again asked the chef de ville and was allowed to camp on his compound. The chief had Parkinson’s and while we were dipping our spoons together into the common bowl, his spoon clattered continuously on the metal.

There was couscous with peanut sauce.

Inside I thought I’d never eat from the same bowl with a stranger at home and here it’s the most normal thing in the world – it doesn’t even matter to me.

The people were extremely friendly. I was absolutely welcome. Although Muslims, men always shook hands with me. I was often offered water in a plastic cup as a greeting. Everything is very uncomplicated.

There was a crowd of small children who received Koran lessons that evening. In general, there are so many children here, really unbelievable.

In this short time in Senegal I probably had more babies on my arm than in my whole life put together. There is no fuss here on how to hold a baby, nobody questioned my ability to look after a child. No one hid their child in a pram or kept it away from the others because it might get sick or somebody might do something wrong.

Everything is so easy here. There are no clever books on how best to change diapers or what kind of porridge to give after a certain number of months. Also, there are no pacifiers or toys.

The babies are simply present, play in the dirt and make a lively impression.

Again, I was allowed to take bucket showers. This time with a privacy screen you stand behind a kind of corrugated iron wall and wash yourself.

The great thing is that there is no need to squeegee the tiles dry after showering, because there might be lime stains, no, just empty the bucket over your head and that’s it. Simple and the way I like it best.

The whole of life takes place outside. Young and old together. A real cohesion.

It wasn’t far to The Gambia anymore. All tarred roads – a stone’s throw away. Easy.

Fascinating glimpse. Heike, what a treat to get a small glimpse of so many different characters and personalities, through your wonderful portraits. So much can be seen just in the variety of eyes and expressions you’ve captured. Really impressive set of photos and photographic skills, and people skills. The trust, comfort and patience directed toward you, while behind your camera, says a lot about you.

Impressive too, is the simpler life revealed, easy going relationships, friendships, love. Some may look at the setting and think, poverty, but I see riches and well in so many ways here in comparison to our Western way of life.

Thanks again, for taking us along and letting us glimpse another small part of this amazing world. Cheers !!!

Dear Ron, you won’t believe how much I always love to receive your wonderful comments!

Thank you! Best greetings to Arizona…..

Heike

Fantastic! The photos, your experience put into words, all amazing to see and read! I am glad to follow your adventures!

Thank you very much Tiffany 🙂

Best greetings from Africa…….enjoy life 🙂

Heike

I have a Senegalese friend here in Houston. Interesting to see his culture through your eyes. Great piece of journaling, Heike.

Thank you very much Angelo!

Best greetings Heike

Wauw, again a great story of you. You are really a tuf woman to do this – chapeau!

I like very much your photo’s of people, with the nice African colours in there fabrics, the bush, the villages: really amazing.

I hope you will like The Gambia. We have been there several times and the people are great, always enthusiastic and a lot of humor. There are a lot of NGO’s and other people from the Netherlands with helping programs. The nature is great there.

Maybe you have time to visit Marakissa River Lodge of Joop and Adama Hermse. They are lovely people and Adama is the running mate for the poor village.

Have a great time in The Gambia!

Thank you very much Dory,

I already left The Gambia – I am not up-to-date with my blog right now 😉

I loved THe Gambia 🙂

Cheers Heike

Fascinating to follow you over the years see how your pictures and stories just getting more amazing with every post you make.

Great to hear I am still improving! Best compliment you could have given me!

Best greetings Lars……cheers Heike

Tolle Fotografin!

???

As always, so impressed by your travels, the stories, but especially the photographs, which are just perfect. Keep riding, good luck and stay safe. Ian

I stumbled onto your blog on Horizons Unlimited and I’m hooked! Your writing and photographs give a real insight into people’s lives. I’m heading the same way next year on a motorcycle so learning lots. Good luck and safe travels.

How I wish I had taken that route. As you know, I cycled all these countries too, but in a rather straight line, quick and I did not sleep often with the locals. I am jealous now, because I think when cycling anywhere, you need to connect with the local people. Only then can one get a total picture. You did that beautifully, Heike! But I also know very well why I avoided staying with locals often…. The sounds, the constant lack of privacy, the non-stop being looked at, not being able to silently read or contemplate. On the other hand, this are chances to make excellent photo’s and, more important: to connect with the people. And you did that so well Heike. You really give something back to the locals. It’s a beautiful exchange system, in my opinion. They feed you and let you take part in their daily life, and you give friensdhip for as long as it last. That, to them and you, is not to measure in money. Africa is so photogenic and you captured it! Well done!!

Thank you very much Cindy – receiving such a positive response from a like-minded person and long term traveler means a lot to me!

Yes staying with locals can be tough, indeed. But my curiosity always draws me to their homes. I simply love to see and understand how other people live and think! And as you said it always pays off.

When I had the feeling the people were poor I shared what I had or walked to the next store and bought food. But as you know people often want to invite us and are very happy to have a traveler around entertaining them…..

Best greetings to Spain……Heike

I read your stories like a little kid on Christmas. I love them. I’m hungry to see life in Africa. Now I’m in Serbia, next stop is Morocco. Thank you for your writing!

Glad you like them……enjoy your travels…..best greetings Heike

Dear Heike!

This is a my post to you so fist of all I would like to thank you so much for the type of work-life that you do-live )) Reading and looking at pictures that you post help me and stimulate me – I am one more confirmed fun of yours.

Also, very impressive that you take time to asnswer many posts in a detaled manner!

Next point is that in my opinion format that you use as simple as it is (long page with a lot of pictures + diary + observations + some philosophical notes ) works great!

But ! And I finish with question-suggestion … I searched and failed to find any video documentory in a “similar spirit” about a life in Africa from “slow independent traveler” like you …

Have you try express all this into video? Have you found anyone doing this “well” ? Maybe among your biking tribe? Are you planning on trying this? Maybe you should try?

Thank you, Heike!