Golmud is a faceless city with a youth hostel where I looked forward to a shower. But – who would have thought? – I heard those familiar words again: “mei you”.

“No! That can’t be true” I thought. Other rules were obviously in force in the Qinghai Province and foreigners weren’t even allowed to spend the night in a youth hostel.

“You could sleep in the park across the street” was the opinion of several people who had now become involved in the discussion, because there was only a single place where foreigners were allowed to spend the night and that was in a 4-star hotel. The park was locked with a gate; climbing over it would be no problem, but I wouldn’t be able to lift my bicycle over the high fence.

“Could I put the bike somewhere in the youth hostel?” As you might imagine, the answer again was “mei you”. So, with that I rode the bicycle out of the city at midnight with the hope of finding something – anything – else. And I got lucky; in a guest house they didn’t know the rules, so I was able to stay there, cost-free, and I was finally able to enjoy a hot shower.

The next day I attempted to send some postcards to Germany. Even when I held them under the noses of the people and showed them the symbol for envelope and stamps in my picture dictionary, they didn’t understand what I wanted. But eventually I was able to find the Chinese post office. I gave my postcards to the clerk and indicated that I would like to buy stamps and that the postcards should go to Germany.

A Chinese person had already written “Germany” in the address section for me. But what did the lady do? She stamped the postcards for sending without any stamps on them. “Uh, excuse me,” I said “and pulled a few crumpled Yuan banknotes out of my pocket to let her know that I needed to pay for the service.” She waved me away with the words “mei you”.

I needed to go somewhere else, but where? I sat out the matter because I had learned in the meantime

that if you just sit and wait, eventually a door would open and something would happen.

And that was how it was. She made a phone call, a discussion ensued and suddenly she asked for some money. Eventually, the postcards were put into an envelope together with the money – but who knows what would happen with it next? In any case, I could never be sure whether the postcards would ever reach their goal.

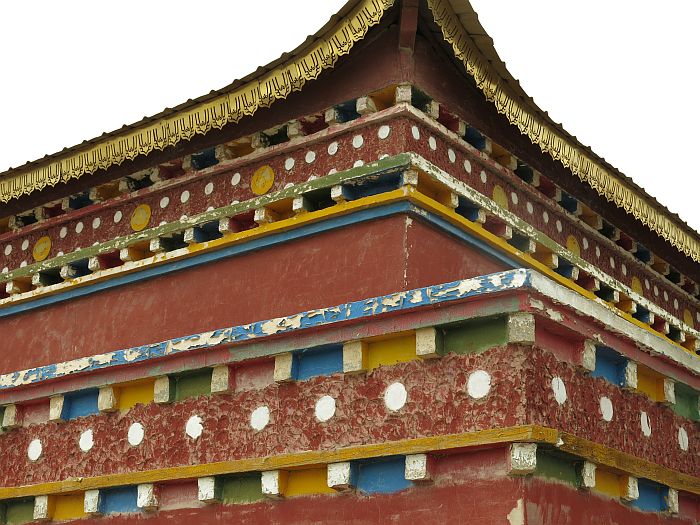

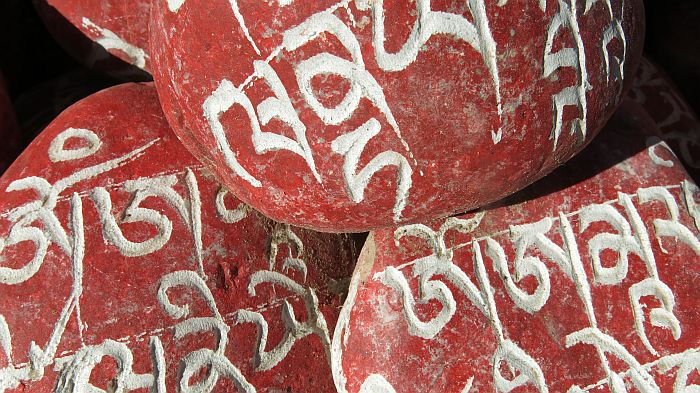

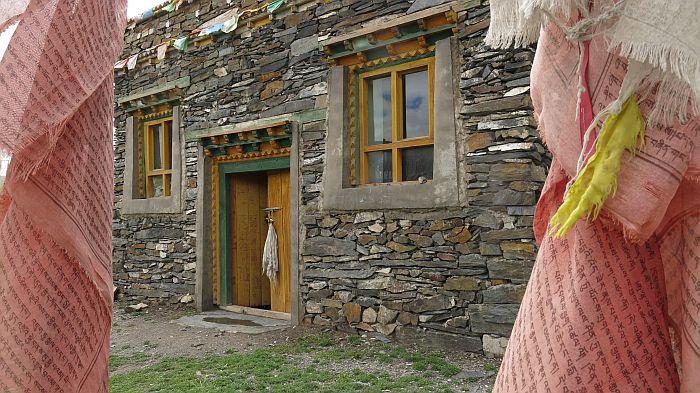

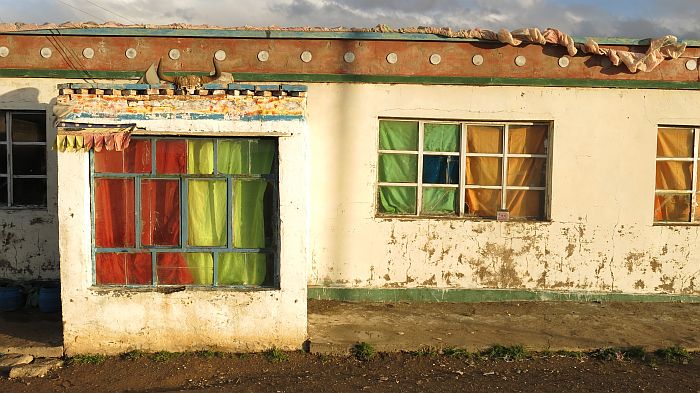

In Golmud I saw the first Tibetan faces and outside the city, I discovered the first prayer flags and Buddhist temples. In addition, I greeted the first Tibetans with “Tashi Delek“ – the greeting of the Tibetans. Wow! Tibet wasn’t far anymore.

But, unfortunately, as a foreigner, I was not allowed to travel into Tibet. In China control is everything. Only with a guide and never as an individual tourist was anyone allowed to travel there.

Beginning with Golmud, the traffic increased significantly. There was no longer a highway and the side strip on the road had disappeared. Trucks, many big cars and endless military vehicles crowded the road. I rode for 2 days past military casernes and troop exercise areas. The road went straight to Lhasa and, in addition to the normal traffic, there was a stream of Pilgrims on it as well.

I also met many Chinese cyclists on their way to Lhasa.

I joined three Chinese students, who had purchased their bikes in Golmud and had

never before left their home town. We all had difficulty with the altitude, for we had

now reached 4,000 meters. The first night I slept in an office while the guys stayed

in a smelly machine room. The second night, we found a dorm at a petrol station.

It was extremely interesting to observe how the boys lived. They had one box of medical

provisions for 14 days with them, which was 3 times as large as mine, but they had

no tools or spare parts. With every meal they took a lot of pills. They also consumed

vegetables from sealed packages and, again and again, some kind of chemical stuff.

They were well-stocked with brand-new clothing, including the Jack Wolfskin brand.

Chinese bicycles don’t appear to be very stable, because constantly something would

break and they were extremely happy that I had everything with me to repair them.

It became consistently colder and rainier. The highest pass of my journey now went up

to 4750 meters. Going up, I didn’t really realize that I would soon have difficulties, but the

longer I was up there, the more headaches I got; then, suddenly, I started freezing.

On top of the pass, the mood was like the festival of the year. There were screaming

Chinese tourists everywhere, all throwing shredded paper around them. I hoped

the ride downhill would be a long one, but I found that the next town lay only

about 200 meters lower, much too high actually to become acclimatized to the altitude.

At this point, we parted our ways because the young men continued on toward Lhasa

and I turned off onto Road 308 toward Yushu. My headache became consistently worse,

so I looked for a place to stay. The little town was horrible – a lot of dirt and unfriendly

inhabitants, rip off prices and only strange people.

They wanted 50 Yuan (about $8) here for a bed in a room for 5 people that looked

like a home for rats. I didn’t feel like sleeping in the same room with 4 other Chinese

men that were all smoking, either. I looked further down the road and discovered

a house in the far distance. I entered the restaurant that was attached to the house

and, to my delight, I saw only Tibetan faces there. They smiled at me and I was

greeted with a hearty “Tashi Delek”. Wow! It was suddenly a completely different

atmosphere. I received a beautiful, clean room for 40 Yuan and was invited to

drink tea with them.

The lady of the house was a very beautiful, elegant lady who walked upright.

Her quiet and friendly manner impressed me greatly. We didn’t speak a word

with each other, but were able to communicate well with our gestures.

All the people here were radiant with a quiet and peaceful appeal. There was

no loud talking and no rough tone of voice. Instead they dealt with each other

respectfully and carefully.

It was a completely different world than in the previous places.

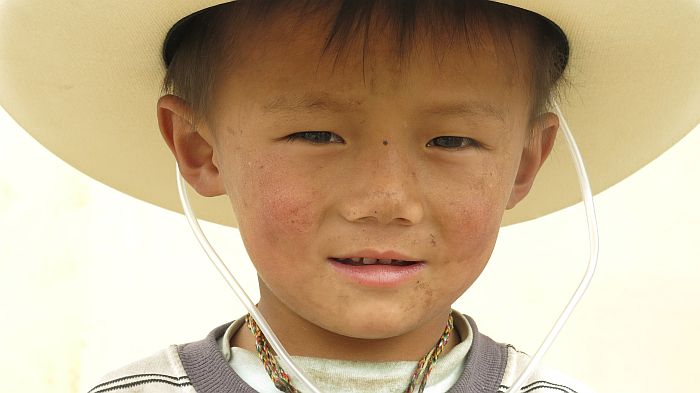

Tibetans look somewhat like North American Indians. They wear strikingly elegant clothing with beautiful jewelry and you really have the impression that their appearance is extremely important to them.

The lady of the house pointed to a poster on the wall with the city of Lhasa. I tried to explain that I was not allowed to go there, and for the first time on my trip, I placed my passport willingly into her hand to show her on my visa that I was not wanted there by the Chinese. I knew she would treat my pass like a treasure and that is exactly what happened. I have never seen anyone handle it as carefully as she did.

Her daughter could read and write the Roman letters, Sanskrit and Chinese. Very impressive. She wrote down the places for me that lay on my route, including the distances in kilometers. Everything was exactly correct.

ended here, and now it continued onward on a dusty corrugated road. I still had a

headache and every bump on the road made it worse. I could hardly breathe

and my condition was sinking rapidly. I simply couldn’t make any headway.

I was truly tormenting myself and was taking more time resting than cycling.

Every time I sat down, I would fall asleep briefly.

The altitude brought me literally to my knees.

Every truck that passed me threw up so much dust that I had to hold my breath

each time to keep from constantly chewing on sand and, afterwards, I had real choking

spells because the oxygen was suddenly taken away from me.

30 endless kilometers I cycled and pushed my bike in tiredness, toward the East.

I couldn’t make it any further that day; it began to rain hard and I hid myself

in a large sewage pipe.

Soaking wet I was given a room for me alone and was also allowed to join

the workers there for supper. The workers sleep here – 6 in a tiny room.

They work together, eat together, sleep together and when they go to the toilet,

they can’t even lock the door behind them – and that for months at a time,

every single day. But somehow I get the impression that it doesn’t bother

the Chinese at all. They are accustomed to being together with other people

all the time. There is no privacy at all.

and had the feeling I was choking. Every time it was almost like having a

panic attack. Regardless of the pain pills, I had a droning headache.

Normally I would have ridden down to lower altitudes, but I didn’t have

that option here. The entire stretch of the road to Yushu was between

4200 and 4800 meters.

With a brutal wind and muddy roads, I continued onward the next day. I was so tired

and exhausted that it was pure torture for me.

For several days in a row, I had one or two flats per day on my rear tire and I tried each time to find a reason for it, but I could never figure it out. On this day I had enough and exchanged the old tire for a brand new one that I had been carrying along with me since Erzurum in Turkey. Although the treads on the tire were absolute super, the tire itself appeared to be disintegrating, after only 13,000 km. The front tire had taken me some 30,000 kilometers already.

Various people came and went endlessly to and from his house. All were Tibetans – beautifully dressed and with wonderfully magnificent jewelry, whether it was a man or a woman. With their cowboy hats they sometimes looked really funny.

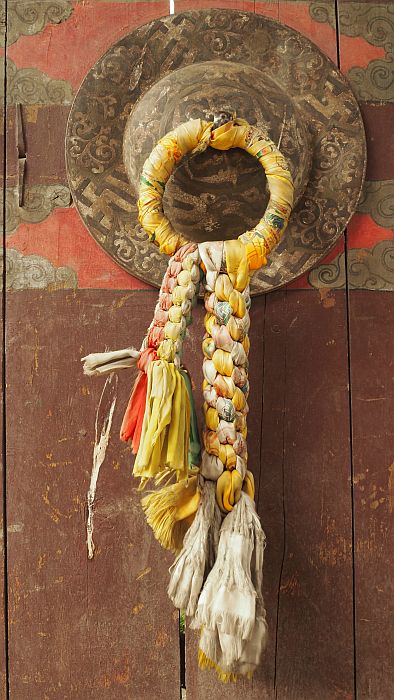

In the room, butter candles were burning. A picture of the Dalai Lama hung on the wall and in the background Tibetan music was playing. He gave me some Yak tea, luckily, without butter or salt. Instead, only black tea, Yak milk and water. Even though it was no treat, it was drinkable. Tasteless,

pastry dripping with grease was offered together with it.

at all. I could barely breathe and sat half the night by an open window listening

to the endless barking of the dogs in the street and tried to calm myself.

began to rain the minute I rode off. I was struggling, not only with the condition

of my health, but also, the way I was feeling, with my own reasoning to continue ahead.

I was hoping for improvement – in the condition of my health, and also in the road

I was traveling on and the weather. But the road was nothing but pure mud.

It was simply gross.

Again and again I stopped at the side of the road near the tents of the road workers

with the hope of getting some hot tea and something warm to eat. They always

supplied me generously and were super nice to me. They live in much poorer

circumstances than the factory workers, because for months on end, they live

in dirty tents with one oven in the middle surrounded by pure chaos. It was

the middle of August and sometimes it snowed, hailed or rained, and to top it all off,

the strong, relentless wind blew constantly. It was icy cold and these people had

my complete sympathy, because they worked not only in the summer,

but also had to live in these primitive tents in other seasons of the year.

To escape the rain and wind, most of the time I would entrench myself in a sewage pipe

under the road and pitched my tent in those protected areas. Everything was wet and

clammy and I began to hate it. It was pure torture.

Later, however, the weather improved and, in combination with the strong wind, the sun dried the mud quickly and transformed the road into a totally dusty trail again.

Unfortunately the truck traffic was so uncomfortable due to the roadwork that I had to constantly convince myself not to give up and ask someone for a ride. If I hadn’t been so stubborn, I would have done that, but I wanted to make this trip by riding my bicycle every single meter.

Tourists, 2 Belgians and 1 Brit, stopped their car and entertained me with a 10 minute conversation. Wow, the first discussion with Westerners since Hami. They told me the landscape after Yushu would improve. I answered by saying “that is really comforting because it is only 400 kilometers away from here.”

Normally, it would only take me 3 days to get there, but under these conditions it would probably take me 8 long, ice cold, wind-blasted, miserable days.

There were so many wild animals here that, regardless of the cheerless conditions,

I was delighted when I would discover a fox, gazelle, marmot or a kiang (Tibetan wild donkey – prevalent in this region) that abound in the endless grass steppes. Hamsters ran continuously from one hole to the next. I saw eagles, cranes and even vultures that it became part of the daily cycling routine.

There were more wild animals in this area than I had seen since beginning

my journey in Germany and that kept me going and motivated me with every new day.

During the night I spent under the open window, I had gotten a sore throat from the breeze on my neck. I couldn’t turn my head without pain anymore and I couldn’t find a pain-free position on my bicycle. At night, an attempt to lie comfortably on my sleeping mat became a nightmare.

Somehow it was impossible for me to get enough sleep at all.

breathing remained. The distance I could travel each day was only 30 km

at the beginning and then, eventually, increased to 50-60 kilometers.

Remembering that only about 10 days before I had reached my record of

180 kilometers and 2500 meters altitude gain, that was a bitter collapse

in my performance. Although, I must add that you can’t really make a

comparison, because previously, I was riding on a smooth asphalt highway

and now I was riding on a miserable road.

One evening, in the pouring rain, I found a small dry spot for my tent in a sewage canal

that was already mostly filled with water and I cooked myself a horrible tasting

instant soup. As I crawled into my clammy sleeping bag with a sore throat,

difficulty breathing and everything wet, I thought for the first time

“you have really reached the bottom. You are 42 years old and now you’re living

like a rat in a sewage canal.” I was hungry but had nothing more to eat,

because for days, there was no place where I could buy anything. That evening,

I had reached the end of my rope.

If it had been possible (as in the Star Trek movies), I would certainly have gotten

the idea to say “beam me up, Scotty”. But there was nothing to do; that option

wasn’t available; so I swept the idea aside and attempted to fall asleep.

The next morning the wind stopped for a while and the sun came out. Road workers

invited me to a warm breakfast and a motorcycle driver pulled me a short distance up

the next pass by allowing me to hold on to his bike. Afterwards came a long downhill

ride and there was a shop in sight. Frequently, after a miserable day, a sunny morning

would appear and the world would become colorful and full of life again.

I had reached Qumaleh and I was looking forward to a shower, a warm room, good food

and, more than anything else, a time to rest. For 100 Yuan (about $16) I stayed in a

hotel that reminded more of a nut house than a hotel. I hadn’t seen a shower in 12 days

and in this hotel there was none. At least in the town there was a public shower place.

The hotel was filled with loud and somehow completely crazy people. The Chinese

are simply incredibly loud. Constantly, they were yelling and slamming doors.

Next to my window was a generator which was always running and barking dogs

ran past my window the entire night. There was no way at all to feel relaxed there.

I had to go on. After I had taken so long for this road, my visa was about to expire again

and time was running out on me. I had barely left the town when I found myself on an

asphalt road. It was 50 kilometers to the next town. Wow! That was purely refreshing.

I treated myself again to a night in a nice hotel and then continued on my way the next morning

It began to rain again, a storm appeared, and again I had to ride over an endless number

of mountain passes. And again, the road turned into pure mud – the asphalt was far

behind me and it rained non-stop. So what? There was nothing to do but squeeze

my cheeks together and ride on.

I looked like pig as I rode into the next village covered with mud. I had no money left,

because there was nowhere to exchange it. I went straight to the police station

and tried to explain my situation. The policeman, a Tibetan, invited me immediately

to a restaurant and arranged for me a bed in a room at the police station. He also

gave me some money so I would have enough to make it to Yushu – a super nice man.

I reached the highest pass at 4797 meters and it wasn’t much further to Yushu;

that’s what motivated me to continue. I had to be there at the latest by Thursday evening

because I had to go to the PSB (police security office) to ask when I could request

an extension for my visa and because it was only eight more days before the expiration

date. Whether I would actually get a second extension was still written somewhere in the stars.

On a Thursday afternoon at the end of August, I rolled soaking wet into Yushu. I was

clearly relieved and completely exhausted from the most strenuous trail in my life.

I had 750 very long, never-ending kilometers behind me. Even my trip in Iceland

was like a children’s birthday party in comparison.

I arrived at the youth hostel and fell dead tired into bed.

At 9 o’clock in the morning, I stood in the office of the PSB.

“No, sorry, unfortunately we can’t give you an extension to your visa in Yushu.”

I was told to go to Xining. They were very polite officials and I believed what

they said. I was sent to another office in the city, which I looked for more than

an hour even though I had the address written down in Chinese characters.

There, I was given the same information and that Xining was the next possible

location. Xining was about a 17-hour bus trip from Yushu away. As you can imagine,

I was overly excited about making that trip.

After a devastating earthquake several years before, Yushu had cleaned itself up

and was rebuilt into a modern city. The many Tibetans who live here didn’t fit at

all into the modern city which surrounded them.

ATM that would accept my bank card. Not only that, but not a single bank

would exchange my dollar banknotes into Yuan. Repeatedly, I heard “mei you”

and, most of the time, I was ignored by the bank tellers – out of shame,

I think, because no one there knew what to do with me.

“You should go to Xining and exchange your money there.”

were sending me there to exchange money. Only one of the bank employees

spoke a little bit of English and I explained to her that I couldn’t go to Xining

without money because I couldn’t pay for the bus ticket. I felt extremely lucky

when she exchanged $50 into Yuan out of her own pocket.

I left my bike standing with all its luggage in Yushu in a fancy hotel in the luggage

room and boarded the bus to Xining.

0 Comments