I crossed the border from Sierra Leone to Liberia (MAP) quickly and without issue, my visa, which I had arranged through an agency in Monrovia, was ready to pick up at the counter. Organizing it online, I had saved myself the detour to the embassy in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone.

Even though the visa online had cost an extra $50, I found it was worth it. Altogether it was $150 for 30 days, which is not a bargain.

Something of interest I encountered in West Africa are the moneychangers. Not only at the border, but also in the larger towns. Money changers, in general, are nothing special, but what fascinates me is how openly they leave their money lying around.

There may be several hundred dollars out in the open on their tables, which for many people equals more than a whole year’s salary; even so, the owner seems to think nothing of it when he goes off to have a coffee. Nothing ever seems to go missing; otherwise, they wouldn’t be so casual.

I also see them occasionally with huge wads of money, loosely stuffed in their pockets. You have to put that in perspective: this would be like walking down the street in Germany with fifty thousand Euros stuffed in your pockets. We would be nervous walking from the door of the bank to our car.

I love it when people trust each other. I trust these people too. I leave my bike wherever I choose and not once have had the feeling that someone here would want to rummage through my bags or cycle off with my bike.

Not long after riding away from the border, it became obvious, people here were better educated than in Sierra Leone. Communication was now relatively easy. Almost immediately, I began hearing the familiar question, “will you take me to Germany?”

The guys knew our soccer players much better than I did. They knew Angela Merkel, and they also asked me reasonably meaningful questions about Europe and possible job opportunities.

What a relief, people weren’t begging here in Liberia!

And I must say, I was very happy not to have to explain everything ten times like I had to in Sierra Leone. I also decided to take a break from remote areas, with the hope; riding the main roads would bring me in contact with more educated people, I was desperate for intellectual conversations.

Although Liberia is also among the poorest countries in the world, my impressions from the start were positive.

Funnily enough, I had often heard that because of slavery and the influence of the Americans, the people here are supposed to have an American accent in their English. When I heard the first Liberians speak, I could only laugh out loud, because their pidgin English, also called Liberian English, has really nothing to do with an American tongue.

Sometimes it’s even very hard to understand. Something Liberians do have in common with the Americans is their love for the flag, especially since the two flags look very similar. They are flying almost everywhere, just like in the USA.

The first night I spent with the police, again sleeping next to the cells, but this time there was no prisoner. I was shown a small empty room where I could pitch my tent. Like every night, there was no problem at all.

West Africans are extremely relaxed. There is always a solution for everything, and I find this great.

Just as much rain as in Sierra Leone, the rainy season was in full swing. Peak month in Sierra Leone was in August, peak month in Liberia with almost 800mm is in September, exactly the months I was there.

It was not far to Monrovia, the capital of Liberia. The road was in great condition, perfect blacktop, so I was able to move forward quickly.

Shortly before the gates of the capital, by pure coincidence, I was able to stay overnight in a children’s home run by missionaries. Nuns and so-called aunties came from all over the world and took care of about 30 children.

The special thing about the institution is that the Italian founder of this organization had developed the concept that one has more understanding for other people in need if having suffered themselves.

The caregivers and nuns had all faced difficult times and situations in life and had received help through the organization for years and now were passing on their love and care to others.

Here were people strong in their beliefs, extremely friendly, and warm, living together in a community, dedicating their lives to the children in their care and God.

I am always impressed with such people; their obvious happiness and sense of fulfillment, along with the good coming from their life’s work, somehow is even a boost to my batteries.

Whether I find missionary work good or bad, let’s leave that out, for now, the satisfaction of the caregivers and the conviction in their work was impressive to experience.

When I said goodbye after a few days, they all stood in the yard and clapped and sang and wished me a very special “Farewell.”

Filling up with energy, comfort, talking, good food, and being part of a community is always good. But I would certainly find it difficult to stay somewhere longer. I am a nomad, and as soon as I have been somewhere for a few nights, I have to move on. This drive has softened some but is still deep inside of me.

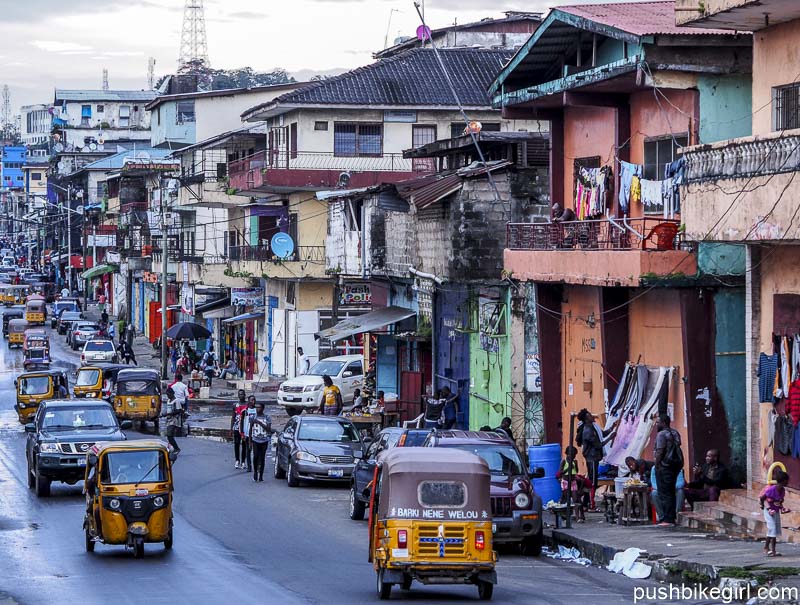

As it did so often, the rain came down by the bucket when I rode into Monrovia. The roads were completely flooded. It was chaos.

Manhole covers are apparently stolen from time to time, leaving dangerous holes hidden beneath the flooding, holes the Tuk-Tuks or KeKehs as they are called here fall into blocking traffic, and adding to the general chaos.

I was also unsure whether I would always see the holes in time? The water was so high in places that I was a bit worried.

Dripping wet, I rode into the city, and I have to say it felt a bit like New York City. Not because everything there was modern and somehow resembled Manhattan, no for sure not, but because after all the muddy battles and the bitterly poor areas, it was great to have the feeling of being able to participate in such a lively atmosphere.

Monrovia was “my” New York City, and although I don’t really like cities, I found this one to be just brilliant.

I’m sure if I had flown straight here from Germany, I would have thought, what a hellhole this is, but for me, it was a much-appreciated oasis of pleasure and renewal.

This is another example of how relative experiences are and how difficult it is to compare one’s own experiences with the experiences of others.

Suddenly there were supermarkets full of delicious products, shelves full of really expensive goodies but I didn’t care about the price at all in those first few days. I was like a kid in a candy store, unable to decide what to buy first.

Of course, the supermarkets were only for expats; they were far too pricey for locals. I was bumping into foreigners finally in and around these stores. I tried to start conversations with almost everyone, bending their ears relentlessly because I was so starved for conversation.

But of course, as always, I still supported the locals and bought fresh papayas, pineapples, bananas, and coconuts at their tiny stalls. Monrovia was paradise on earth. I had an absolute permanent grin on my face. So many delicacies that I hadn’t been able to enjoy for months.

I lived in a convent, the cheapest accommodation in town — a room with electricity and toilet along the corridor for 20 Euros. Monrovia was extremely expensive in relation to people’s income.

This is mainly due to the fact that Monrovia has no working electrical or water supply infrastructure. A capital that is almost dark at night.

Only the hotels, embassies, and the wealthy can afford to produce their electricity with generators, and that is extremely pricey.

Next door was the sea, and the way to get there was through the Coconut Slum. Of course, I was warned not to go there, because it is supposedly dangerous, but I don’t listen to such statements all that much anymore.

The Coconut Slum will probably be one of the places in the city that will remain in my memory the most. I ate my meals there every day in the only small wooden shack and found the atmosphere there very exciting.

So far, I have found the Africans – apart from the people in Guinea-Bissau and the Moors in Mauritania – to be extremely friendly. Liberians put a crown on the whole thing.

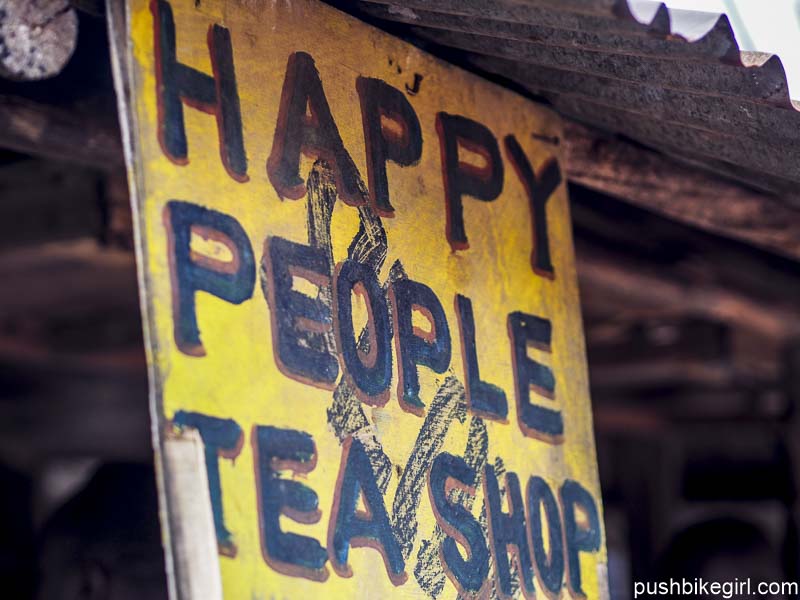

Even in a capital city, where normally nobody talks to anybody and people are much too busy with themselves, I was able to talk to the whole street. Within a very short time, I knew the people, vendors, shop owners, kids, and my daily tea guy. I love that kind of thing.

Cornell, from the Coconut slum, was allowed to live in one of the ruins for free and told me a little about life there.

“We are 5000 people and share four toilets — two for the women and two for the men. The flushing is done with saltwater from the sea. Our normal water is brought from outside once a week by tanker and pumped into an old pool.

A pool that once belonged to a hotel – before the war, when Monrovia was much more prosperous.

We eat once a day; we don’t have money for more. We take any job we can get, but there is almost never work. Our community sticks together. I like the Coconut Slum; I like living here.

When we are sick, we only have money to buy medicine on the street; unfortunately, there is not enough for the hospital. I’m always worried about my grandchildren and hope they don’t get sick.

When I am worried, I read my Bible, then I sit on the balcony, look at the sea, and get strength through the words of God.

We do not have an easy life, but we live. Others have died in war or from Ebola. Of course, we all hope that our situation will soon improve, but we have been hoping for this for a long time.

Everything was better before the war; we were doing well then.”

Through Mirjam, a missionary from Holland, I met Firmin, a priest from the Ivory Coast, and was allowed to live with him. With Firmin, I could have stimulating conversations.

“I’m tired of the food. I miss my mother’s good food. It costs a lot of money to keep the generator running. Our church does not even have walls, but we try to form a small congregation and give the children a good education.

Only with education we can achieve something. Monrovia is in a catastrophic state: a capital city without light or water.”

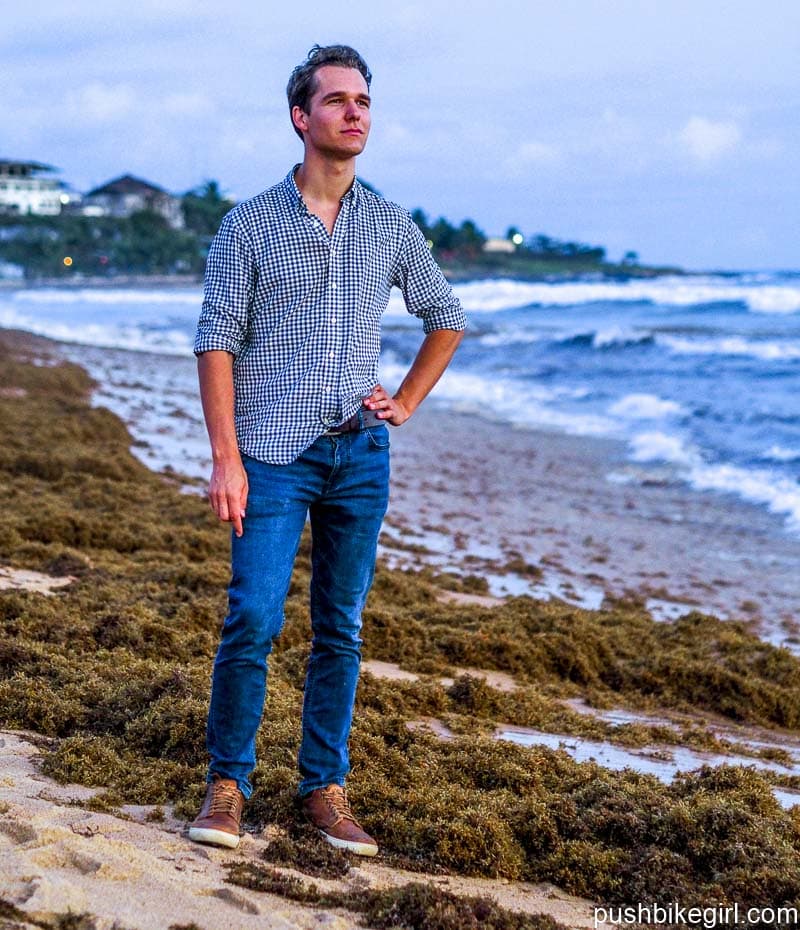

On the way to the Ivory Coast embassy, I met Evan and Meghan, two touring cyclists. Such encounters are, of course, always very special. We spent the whole day together exchanging experiences. We talked about our equipment, made fun of the authorities or gave each other tips on how and where things are particularly interesting.

The visa for the Ivory Coast, my next country, was no problem at all. I got it within one day and for 70 Euros. Mirjam, also helped me obtain my visa for Ghana, having lived in Africa for many years she had the right contacts and knew how to make good use of them.

A huge help as visas for Ghana are not easy to get in West Africa at the moment, so I was very happy that Mirjam was there. I had a full three months to enter Ghana before the visa expired.

Unfortunately, the ATMs were refusing the type of card I was carrying. I tried several machines, but without success.

But I was lucky here, too, because Tom from Belgium, a “Warmshowers” host, was visiting at home, and was able to bring me Euros on his return, which I could exchange for dollars.

Tom works for an NGO..

“My company is part of a large team that is overseeing the completion of a hydroelectric plant that will provide the city with both electricity and drinking water. A development aid project worth several hundred million dollars”.

Tom lives in a posh ghetto: high walls, barbed wire, security guards, and by African standards an exclusive apartment. And so, I “celebrated” my third hot shower since Morocco while staying with him. ?

I was also able to use his kitchen and cooked every day and really enjoyed this opportunity very much. There were even treats like banana pancakes and coconut curry.

Tom also brought me a new chain from Europe, a new cassette, a new camera body, and a Therm-a-Rest mat. The Therm-a-Rest was sent to him by express mail from Ireland to Belgium, and the company did not charge anything for it. Absolutely great!

The box with a new Picogrill Hobo stove, unfortunately, my old one was totally rusted, did not arrive in time. So, I had no stove at all.

Although I couldn’t use mine lately anyway – with so much rain, a wood stove is pretty much useless.

I met Mirjam a few times, and she told me what she has been doing here in West Africa for the last 15 years. She works as a missionary, and when I asked her if she thought that she could make a difference, she just said:

“I have an easy life here. I’m always looking for new projects to get donations, it’s not much, but I wouldn’t know what to do at home, so I’m continuing here.

Sometimes I do think that it brings something. But it’s not easy.”

I got to know Victoria through Laurent, the French cyclist from Morocco. They both work for the organization “Plan International.” Victoria told me about her tragic life story, and I listened to her with great interest.

“I grew up in a slum. It wasn’t easy then. We had more money than others, so they were often jealous. Often when I was growing up, girls and women were abused or raped. My mother also suffered from my father, and so she separated from him.

In 1990 the war started, and we were forced to flee Monrovia. With only the bare necessities on our backs, we tried to escape, but we did not know where we were going. The rebels were only holding me, not anyone else of my family. I was naked, and a knife was held to my back. They wanted to kill me. But I was very lucky and one of the rebels let me go.

In Guinea, we were free to live in freedom. I got married and have five children. I have been a widow for 15 years; my husband died of diabetes. I was homesick, came back to Monrovia, and at the age of 47, I am now doing my master’s degree at the university.

Through the violence I experienced as a child, I am now working for equality. We women must fight; we can no longer put up with being second-class citizens. Too many women are still being raped and beaten, even little girls.”

I spent three weeks in Monrovia, and afterward, I got back on my bike strengthened. Monrovia had been simply great, definitely a highlight of my time in Africa so far.

I turned north and cycled the whole time on the brand-new main road, which was almost completely tarmacked. I didn’t have much time left. I had to leave the country soon because, as so often, my visa was almost expired.

I came to a place and couldn’t believe my eyes. It was market day. The people and their goods stood directly on the flooded gravel road.

The stench from garbage and even the water was intense, but the people didn’t seem to mind. There were so many people there that I could hardly make my way through the crowd.

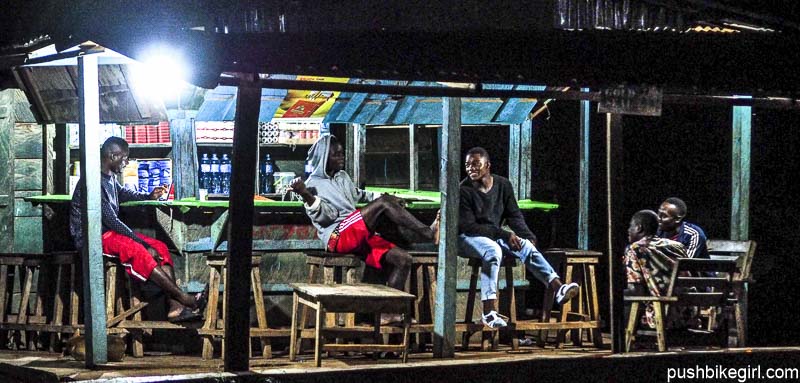

At some point, I saw a television on at a tea stall and was surprised that someone had electricity here.

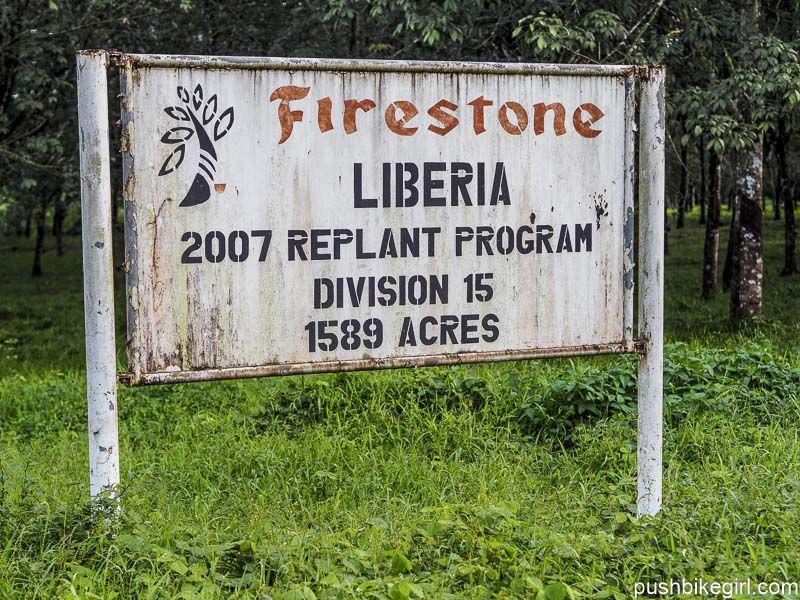

By chance, I then discovered I had entered the largest contiguous rubber plantation in the world. The American company “Firestone” has leased land here for almost 100 years. The company built schools and settlements based on the American model and employs several thousand people.

The capital Monrovia has no electricity, nor does the rest of Liberia, but the rubber plantation, which has built its own hydroelectric power station here, does. The whole area is much more prosperous, and you would think you are somewhere in the Southern States in the US, but not in Africa anymore.

A priest let me sleep in the church and swept the food leftovers from the last service out of the way for me, which were scattered everywhere between the benches. The church even had AC. Funnily enough, for once, no bats were living there; this time, an owl had made itself comfortable.

“Firestone,” an investor who, it seems, did everything right. The priest praised the company in the highest tones.

During my next break from the rain, I had another tea at a tea stall and met a business person.

“We need investors like “Firestone,” that helps us the most, but unfortunately nobody invests in our country. Our president is a disaster; it’s only gonna get worse.

Development aid is not good for us. You can’t give people money for doing nothing.”

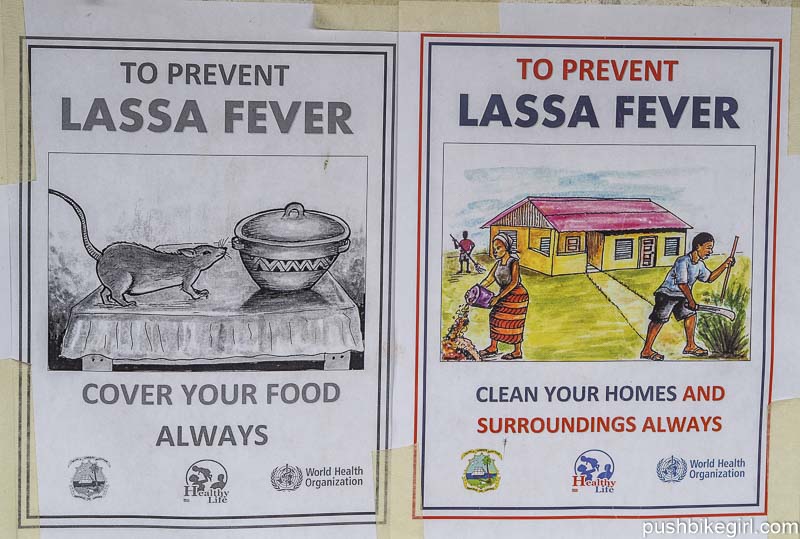

With concern, I noticed a poster about Lassa fever. Liberia is currently experiencing an outbreak, and within the region I was cycling through. Lassa fever is, like Ebola, hemorrhagic fever and often ends fatally.

It is transmitted by a very specific type of rat, which is only found in West Africa.

Teams drove through the streets with loudspeakers and gave people instructions on how to avoid the infection.

As you can probably imagine, I got a little nervous because I couldn’t assess the danger at all.

Soon the area became bitterly poor again. I saw a lot of children with blown up bellies and umbilical hernia. Since Sierra Leone, I’ve seen a lot of this. Sometimes it looks as if the children have swallowed tennis or table tennis balls, which are then pressed out at the belly button.

The umbilical hernias are probably due to the incompetence of the doctors. Flatulence was also prevalent here and is due to malnutrition.

Jim, a missionary from the States, took me in for a night. And, of course, I took the opportunity to ask him a lot of questions.

He has been in the area for ten years, was originally an engineer, but then decided by faith to go to Africa. He teaches religion at a school. He has installed solar panels in his house.

“The level of a graduate here is approximately first or second grade. Of course, not all children go to school. It would be much better if I taught science, but I don’t get paid for that.

I have an easy life here, get along well with everyone, help where I can, and save most of the money I earn for my pension. Whether I really make a difference here, I don’t think so, but I like it here very much.

If I wasn’t here, I don’t know how they would get their solar systems and water pumps repaired within a radius of about 200 kilometers. There is nobody else around who can do that. Outsiders install high-tech equipment here, but nobody knows how to use or maintain the equipment.

It will be the same problem with the hydroelectric plant in Monrovia. It’ll run for a few months, and once problems arise, nobody will be able to get it running again. Development aid without a concept.

I am against development aid anyway; it doesn’t make any sense at all. I also think all white people should leave Africa immediately. Then we’ll see what happens.

White people often say that the colonies are to blame for everything, but Liberia has never been colonized and is still one of the poorest countries in the world.

The lease for Firestone will, unfortunately, expire in the next few years, then the president will surely manage to put so many obstacles in the way of the company that they will leave the country.

I’m the man for everything here. I’ve read up on medicine, give out medications when someone knocks on the door, and asks for help. I try to explain family planning to the girls and know that I know much more about medicine than any doctor in the area.

Young girls come to me and ask me what is wrong with them when they suddenly have a big belly. They do not know that they are pregnant, and they do not know how they got pregnant. And their mothers don’t tell them.

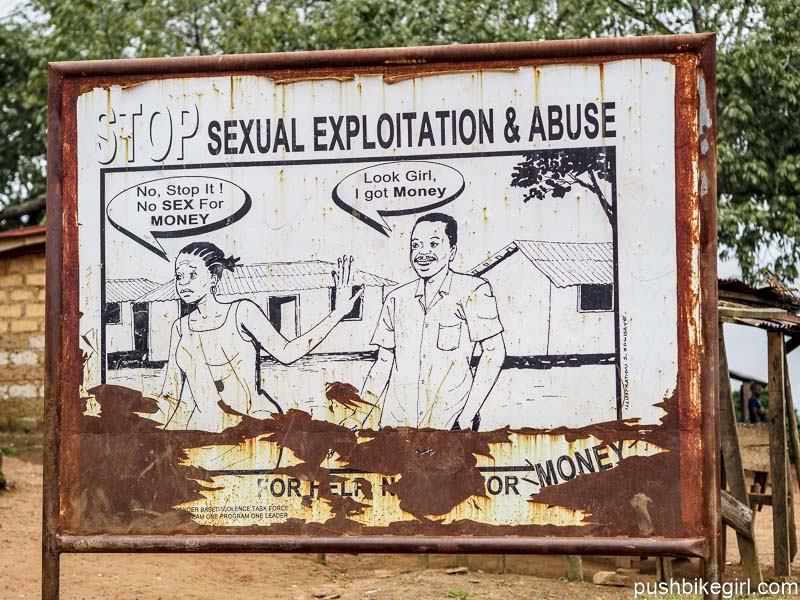

Then when they have their baby at 14 or 15, they look for ways to feed them. We would call it prostitution, but they see it more as doing the boy a favor. The boys get what they want; in return, the girls get money for their child. They see it as a trade.

It’s about survival; the girls need water and food, nothing else matters. They’ll do anything to get food.

People have to share, but they don’t want to share, but the culture demands it from them.

It’s the same at school. The teachers demand money to pass the test, and because none of the students have money, the girls are happy if they “pass” the test in trade for a few minutes of sex.

When they enter into a relationship, it is not about love and caring and understanding; it is about how little they have to invest to get the best out of it.

Even after ten years here in the area, I can’t really understand the culture. It’s all very complex. But I get along well with myself; otherwise, I would not be happy here.

The village chief is in charge here, allocating land to the people. But if he feels like he can simply take away the people’s fields overnight. Maybe because he can’t stand the person anymore, or maybe because he suddenly promised someone else the piece of land.

Then the former owner gets another piece of land, maybe much further away from the village than before. There is then no well, and therefore there is hardly a chance to grow anything.

The villagers shy away from investing because the village chief can decide everything.

In the beginning, when I came here, I also thought that the people were lazy, just sitting around doing nothing, but I don’t see it that way anymore. I see that they try to survive.

The money they can earn in the fields is very little, and so they think it would be better to wait for another chance. So, they hang around somewhere, waiting for a job.”

When we looked for food in the village, he spoke to all the people like a teacher to his students. I guess it’s his way of getting along best with people. I understand that very well, and I often feel the same way.

But for me, that would not be enough in the long run; I could not do it. I need interesting conversation with people, that is the biggest problem for me here in West Africa.

I sheltered under the roof of a pharmacy while fixing a puncture as it was pouring rain. The owner, an Indian, watched me at work and I asked him how he liked it here.

“I like it here very much,” he answered.

“Are you sure?” I asked him.

“No, I do not like it here. The food is bad; the people are very poor. I have no friends here and I’m always alone. But I haven’t been to India for 15 years, I also no longer know anyone back home.

I’ve been to Ghana before, and Ghana is much better developed, such a big difference to Liberia.”

Just before the turn-off to the gravel road leading to the border, people had electricity again. But this time, it came from the Ivory Coast.

Eighty kilometers of catastrophic road lay before me to get to the border. I knew that there was a mud battle waiting for me again. I had a lot of time pressure because my visa expired that day, and so I wanted to reach the border in time.

It was pitch dark as I cycled the last 2 hours, often pushing the bike through deep mud, finally, there I found the border station had closed.

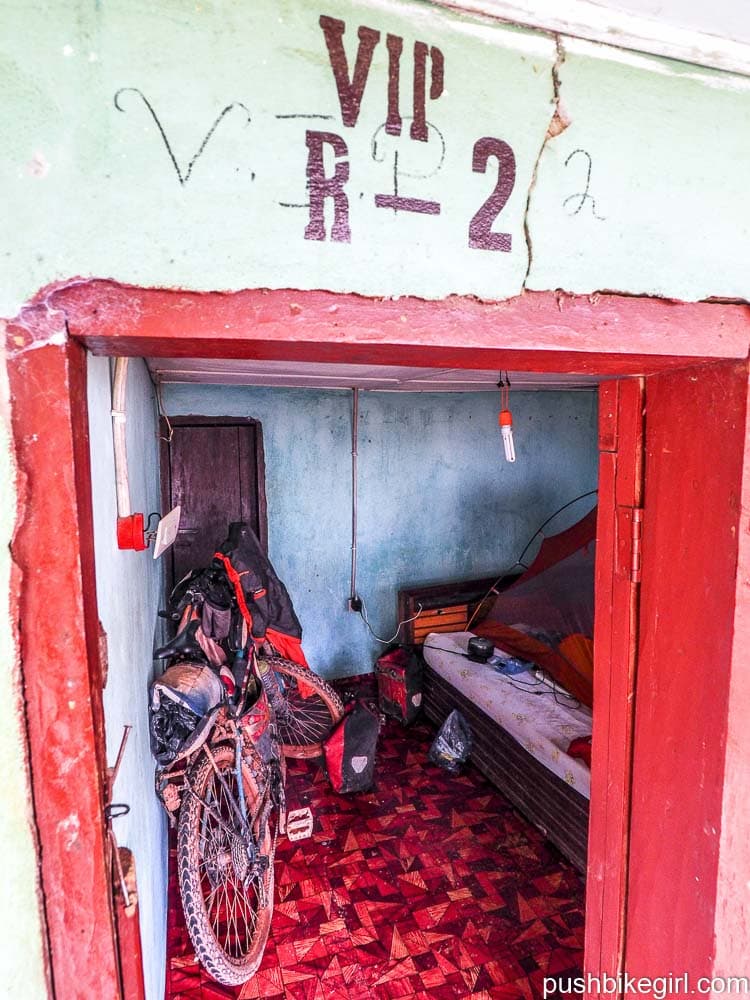

But This is Africa, as we all know, nothing is ever a problem here and so the border police sent me to the VIP hotel, where two boys were showering with their buckets out front.

So, it was the last time I pitched my tent in Liberia – using my mobile home as a mosquito net to protect me from fleas and other tiny creatures on top of a very old and filthy mattress.

Liberia had been really exciting. But I was growing tired of West Africa.

You are very welcome to share the article among your friends – thank you ?

So happy you had this wonderful experiences in Liberia. Hope you will have plenty more. Guess you shoot jpg or do you do RAW?

Hi Lars, big thank you 🙂

I shoot both.

Best greetings Heike

Enjoyed your posting a lot ?just like the previous ones. Glad you enjoyed Liberia. Am wondering what Ghana will bring – hope you will find lots of helpful, smiling people along the way as well tons of meaningful conversations.

Keep having fun, safe riding and may the wind be with you.

Inge

Big thank you Inge!

Glad you like my articles 🙂

Best greetings and thanks for all your wishes…..

Heike

Hallo Heike, chaos, beauty and a bit of trash could subtitle this one. Loved the crazy street scenes, and your unique way of showing your travels.

One of my fond memories from my years in Senegal, was the quiet dignity found in some Africans. They were special, radiated peace, and I always enjoyed being in their presence. I may be wrong but from her words and your photos Cornell comes across as one of these people.

Thanks for taking us along, best wishes

My nomad friend,

Thank you for sharing your journey with us. Your photos and words are so evocative. I wish you continued strength and truly admire your will and brave eyes…

Thank you Pistil 🙂

Another amazing insight into a country so far from my own. I always enjoy reading your posts and it was so interesting to hear directly from the people you met. Can’t get over the ‘beauty from within’ that shines in the faces of the people you encounter. All the best for the next leg of your journey.

Dear Lyn,

big thanks for your nice comment!

Oh yes, the people are so very beautiful and friendly – it is amazing to experience!

Best greetings Heike

Como siempre una excelente observación del lugar y la cultura, junto con tus sensaciones y emociones. Muy bueno!

También excelente el registro fotográfico, buena mirada! Que equipo llevas en tu viaje?

Gracias y saludos!

As always an excellent observation of the place and culture, along with your feelings and emotions. A pleasure to read you.

Also excellent photographic record, good look! What equipment do you carry on your trip?

Thanks and regards!

Again, a really interesting article with great photos. I used to work in the development field, and find it interesting how many people in Africa think development funding is bad. This is also my view, but the politicians don’t want to deal with reality. I am full of admiration for your cycling tenacity as well as your photo-journalism.

The person who said that all whites should leave Africa – was he white himself?

Thank you.

Ian.

Thank you Ian for your thoughts, interest and compliment!

He was a white man from the US.

Best greetings Heike

Danke!

Just when I was growing gloomy over the value of this Facebook phenomenon your latest posting on Liberia appears. What a pleasure! Your writing just as good as the pictures. Thanks so much Heiki!

The nonchalance of the money changers may be the result of their connections. Organized crime networks, government bureaucrats, both. Doubt that’s a position open to everyone with a good head for math and a wad of bills at their disposal.